Hypercinema 9/28/22

In translation

Our synthetic media project for this class (group: myself, Dipika Titus, Dror Margalit) took a few more turns than I thought it might. The extra week of time we got certainly played a role, giving our group more time to move beyond the ideas we had for purely digital or a largely performance-centered experience to settle on what we’re presenting in class today.

In our initial brainstorming discussion, I brought in the inspiration I initially thought I’d work from in solo: Ursula Le Guin’s book The Lathe of Heaven. We discussed several ways we might reinterpret the book’s core plot mechanic, dreams that become reality, as an exploration of AI.

I think the point we kept returning to in these early discussions became the seed of what followed: Dror brought up how he wasn’t interested in constructing a piece that simply pitted something like Stable Diffusion or DALL-E against humans in a battle of creativity. We all agreed that it would be more interesting to make something at served as an exploration of what AI tools are capable of doing in terms of opening up expression and communication as opposed to focusing on what they can’t do very well.

At our next meeting, Dipika recalled a conversation she had toward the start of her time at ITP about language. Someone who didn’t speak English as their first language had described the feeling of having other people listen to them differently, either tuning out or having difficulty following their thoughts as expressed in English. Thats where the title, “I’m smart in my own language,” came from. Dipika also brought up the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which proposes that a person’s understanding and perception of the world is largely shaped by the language or languages they know best. This was our lightbulb moment.

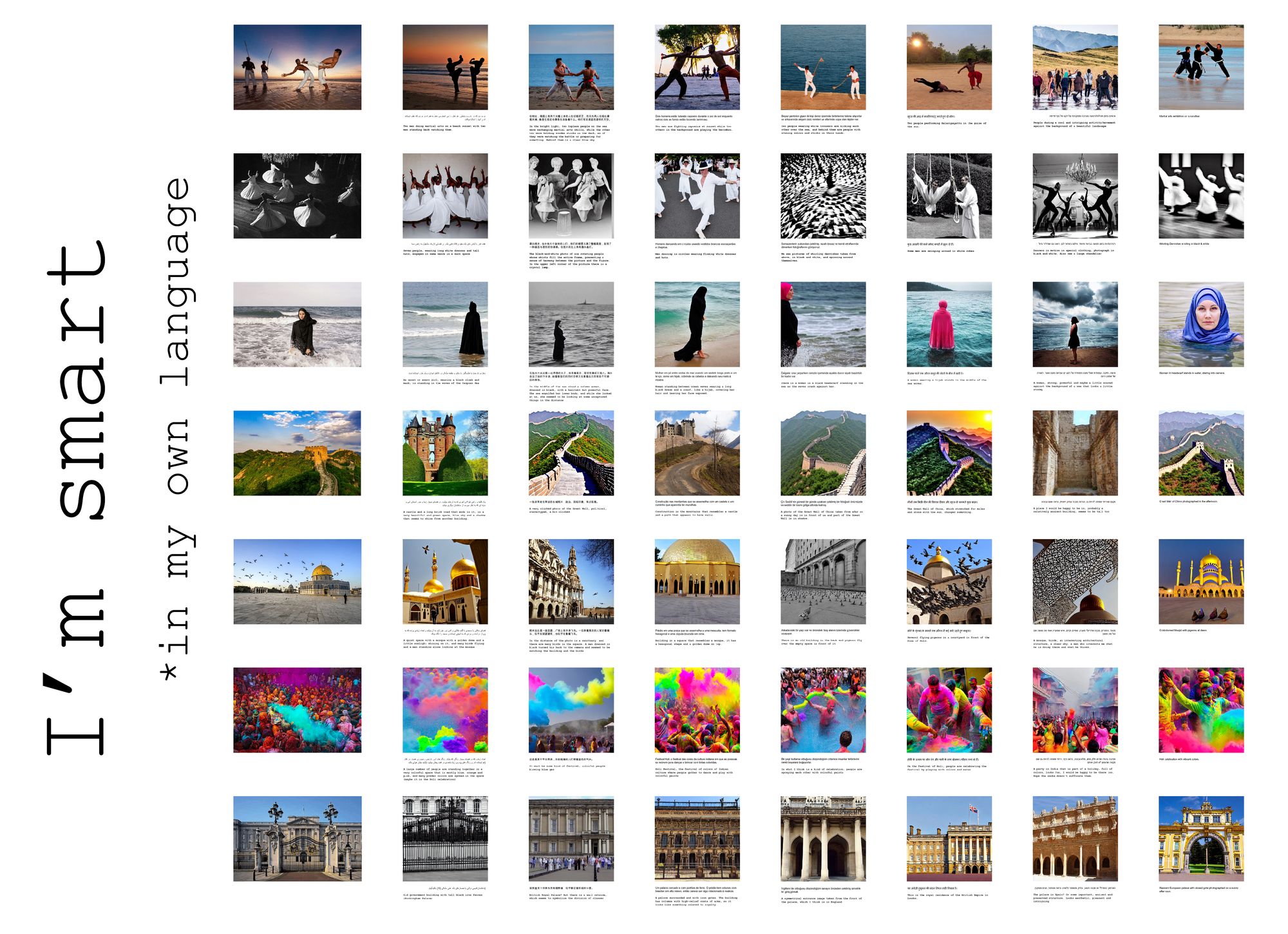

Language as a barrier to access is an issue with tech in so many ways, and the fact the most popular AI text-to-image models are first trained on with English-labeled data, then used with English prompts, leapt out as something worth reflecting on. We quickly came around to the idea of this double AI pass, where non-native English speakers would describe an image and then have those descriptions translated to English via Google Translate before being fed as prompts to Stable Diffusion. We hoped that the similarities or differences between the AI generated outputs would be more striking than the differences between the AI outputs and the original images, steering us away from that realm of pitting AI against human and toward consideration of how AI understands our language and cultural or linguistic frames of reference.

We roughly divided up the work like so: Dipika took point on selection of original photos and solicitation of the descriptions, Dror looked into automating the translation and output process, and I took responsibilities for our final visual presentation.

Initially, when we were still talking about the dreaming concept, I was looking into using Twine as a way to create lightly interactive path through the story we were telling. Once we switched tracks and established that might have dozens of different images involved in our final piece, I proposed that we think of it more like a gallery exhibition that people could take in at their own pace. Initially I envisioned a series of posters, one for each original image and the corresponding AI outputs. This could’ve been okay, but I’m very glad Dror and Dipika’s feedback pushed the design in another direction. Instead, especially considering that the same seven people were giving us the descriptions in each language (huge thanks to Elyana, Han, Mica, Elif, Jagriti, Gal, and Spencer for their contributions), we decided to go for one monumental poster design.

As an aside: wow, it was a pain doing the layout in Illustrator. I’m sure there are tools and options that could’ve made the process easier, but I’m also taking this as motivation to really teach myself Figma to see if that’s a better option for projects like these.

One major issue came up as I was designing the poster that could have sank this project, and I’m so glad we caught it. When I started taking the text from our compiled Google Doc file into Illustrator, I immediately noticed that the Arabic characters were not rendering correctly. Perplexed, I pointed this out to Dror and we began troubleshooting. We quickly realized that simply copy-pasting the text wouldn’t work and would at least require tweaking some obscure language options–on top of Illustrator missing certain characters, the copy-paste process would reverse the direction of the Arabic and Hebrew.

I felt awful at the thought of it: the last thing I’d want a project about language to do is mess up something so basic as that (though yes, it does still happen with groups and organizations that should know better).

The solution I came up with was to set the type in Google Docs, hoping that my modifications in the document there wouldn’t inadvertently alter the original descriptions our participants provided, then export it as a PDF to be sliced up and arranged in Illustrator.

Eden Chinn was a huge help in getting the poster printed using ITP’s Roland large format vinyl printer, though we of course ran into an issue there. The print job stopped part way through the poster, soon after it had printed the grid of all the AI generated images and the corresponding descriptions. This meant what we had was still salvageable–as I went to class after having worked with Eden at the printer, Dror and Dipika took the poster and trimmed off the partially printed bit. It’s unfortunate, but I’m hopeful that the issues with the printer will be worked out soon and that our project will help other first-year ITP students know it’s a resource they can should use!

All in all, I can think of a few things I’d do differently given the chance to work on this again, but I’m really happy with how this turned out. Will edit this post include links to the blogs from Dror and Dipika when available for their perspective on this project.–10/6/22